Article Plan: Selective Mutism Therapy Activities PDF

This comprehensive PDF details therapeutic interventions, encompassing CBT, exposure, and PCIT, alongside practical activities for early, intermediate, and advanced stages of treatment․

It also explores medication’s role, parent/educator involvement, and strategies for generalization, social skills, and relapse prevention, offering a holistic approach․

I․ Understanding Selective Mutism

Selective Mutism (SM) is a complex anxiety disorder characterized by a consistent inability to speak in specific social situations, despite speaking freely in others․ It’s crucial to differentiate SM from simple shyness or autism, as treatment approaches vary significantly․

Understanding the prevalence and demographics helps tailor interventions effectively․ While often diagnosed in early childhood, SM can persist if untreated․ Effective therapy requires recognizing that this isn’t willful silence, but a physiological response to anxiety․

This PDF will explore how to create a safe environment and utilize play-based activities to build communication skills, ultimately reducing anxiety and fostering verbal expression․

Understanding Selective Mutism

This section clarifies the nature of SM, distinguishing it from shyness or autism, and emphasizes the anxiety-driven root of this communication challenge․

I․A․ Defining Selective Mutism

Selective Mutism (SM) is a complex anxiety disorder characterized by a consistent inability to speak in specific social situations, despite possessing normal language skills in other contexts․ It’s not simply a refusal to speak, but a physiological inability driven by intense anxiety․

This manifests as a persistent pattern where a child speaks freely with family but remains consistently silent at school or with unfamiliar peers․ Understanding this distinction is crucial for effective intervention․ The PDF will detail how this differs from typical shyness and how accurate diagnosis is paramount for implementing appropriate therapy activities․

It’s vital to remember that SM isn’t willful defiance; it’s a genuine struggle with anxiety that requires compassionate and specialized support․

I․B․ Prevalence and Demographics

Selective Mutism affects approximately 1% of children, though accurate prevalence rates are challenging to determine due to underdiagnosis․ It typically presents before the age of five, often becoming noticeable when a child enters school․ This PDF will address the importance of early identification for optimal intervention outcomes․

While SM can occur in any demographic, research suggests a slightly higher prevalence in girls․ Understanding these demographic trends helps clinicians tailor therapy activities to specific needs․ Factors like family history of anxiety may also play a role, informing a comprehensive assessment process․

Awareness of these statistics is crucial for educators and parents to recognize potential signs and seek professional evaluation․

I․C․ Distinguishing from Shyness or Autism

Differentiating Selective Mutism (SM) from extreme shyness is vital; shyness involves discomfort, while SM is an anxiety-based inability to speak in specific situations despite possessing the language skills․ This PDF emphasizes diagnostic clarity․

SM also differs from Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)․ While some children with ASD may have limited verbalization, SM involves consistent verbal ability in comfortable settings․ A thorough assessment, as detailed later, is crucial to rule out ASD and other conditions․

Accurate diagnosis informs targeted therapy activities․ Misdiagnosis can lead to ineffective interventions, hindering a child’s progress․

II․ Assessment and Diagnosis

A comprehensive assessment is the cornerstone of effective intervention, as outlined in this PDF․ Diagnosis relies on the DSM-5 criteria, focusing on consistent failure to speak in specific social situations despite speaking freely in others․

Utilizing assessment tools and questionnaires – though specifics aren’t detailed here – helps quantify the severity and context of mutism․ Ruling out other conditions, like shyness or ASD, is paramount, requiring careful observation and potentially, collaboration with specialists․

This PDF will guide professionals through a structured diagnostic process, ensuring accurate identification and tailored therapy plans․

Assessment and Diagnosis

This section details DSM-5 criteria, assessment tools, and the crucial process of differentiating selective mutism from shyness or autism spectrum disorder․

II․A․ Diagnostic Criteria (DSM-5)

Selective Mutism, as defined by the DSM-5, requires consistent failure to speak in specific social situations where speaking is expected․

This disturbance must be more than just shyness, lasting at least one month, and significantly impacting academic achievement, social life, or other important areas․

The diagnosis excludes communication disorders like stuttering, and isn’t better explained by another mental condition․

Crucially, the lack of speech isn’t due to a lack of knowledge of the language, but rather an inability to speak in those specific contexts, highlighting the anxiety-driven nature of the disorder․

Accurate diagnosis is the first step towards effective intervention․

II․B․ Assessment Tools & Questionnaires

Comprehensive assessment is vital for tailoring therapy, moving beyond observation to utilize standardized tools․

The School and Home Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ) assesses mutism across settings, providing a detailed profile․

The Selective Mutism Questionnaire (SMQ) offers a parent-report measure of symptom severity and associated anxiety․

Direct observation in various settings – classroom, lunchroom, therapy – is crucial, noting speaking patterns and anxiety cues․

These tools help differentiate selective mutism from shyness or autism, guiding the development of targeted therapy activities․

II․C․ Ruling Out Other Conditions

Accurate diagnosis requires differentiating selective mutism from other conditions presenting with similar quietness․

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) must be carefully considered; while some overlap exists, SM typically involves social comfort in familiar settings․

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) can co-occur, but SM is specifically context-dependent, not a generalized fear of social interaction․

Language disorders should be assessed to ensure mutism isn’t due to expressive language difficulties․

Thorough evaluation ensures therapy activities address the core issue – anxiety-driven mutism – rather than misdiagnosed underlying causes․

III․ Core Therapeutic Approaches

Effective treatment of selective mutism centers around three core therapeutic approaches, often used in combination․

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) addresses anxious thoughts and behaviors, helping children challenge negative self-perceptions․

Exposure Therapy, particularly systematic desensitization, gradually introduces speaking situations, building confidence․

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) strengthens the parent-child relationship and equips parents with strategies to encourage communication․

These approaches form the foundation for targeted therapy activities, fostering a supportive environment for progress․

Core Therapeutic Approaches

Central to treatment are CBT, exposure therapy, and PCIT, working synergistically to address anxiety and build communication skills in a supportive setting․

III․A․ Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a cornerstone of selective mutism treatment, focusing on identifying and modifying negative thought patterns contributing to anxiety․ It helps children challenge fears associated with speaking in social situations, gradually building confidence․

Activities involve recognizing anxious thoughts, developing coping mechanisms, and practicing relaxation techniques․ Therapists utilize techniques to reframe negative self-talk and promote more realistic perspectives․ CBT aims to empower children to manage their anxiety and increase verbal participation․

Successful implementation requires a collaborative approach, involving parents and educators to reinforce learned skills across various environments․ Medication can sometimes be used as an adjunct to CBT, particularly in cases of severe anxiety․

III․B․ Exposure Therapy – Systematic Desensitization

Exposure therapy, specifically systematic desensitization, is a crucial component in overcoming selective mutism․ It involves gradually exposing the child to increasingly challenging speaking situations, paired with relaxation techniques․ This process aims to reduce anxiety associated with verbal communication․

A hierarchy of feared situations is created, starting with less anxiety-provoking scenarios and progressing to more difficult ones․ Activities might include whispering to a therapist, then speaking to a trusted family member, and eventually interacting with peers․

Success relies on a slow and controlled pace, ensuring the child feels safe and supported throughout the process․ Parental involvement is key to reinforcing progress and providing encouragement;

III․C․ Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is a powerful therapeutic approach for selective mutism, focusing on strengthening the parent-child relationship and improving communication patterns․ It actively involves parents in the therapy process, equipping them with skills to foster their child’s verbal expression․

PCIT utilizes live coaching, where therapists observe parent-child interactions and provide real-time feedback․ Techniques emphasize positive reinforcement and reducing parental anxiety, creating a supportive environment․ This approach is particularly effective when combined with other interventions․

Consistent application of PCIT principles at home is vital for generalization of skills and long-term success․

IV․ Specific Therapy Activities – Early Stages

Early stage activities prioritize building rapport and safety․ Non-verbal communication exercises, like drawing or playing, allow the child to engage without pressure․ Play-based therapy is crucial, offering a comfortable medium for interaction and emotional expression․ Creating a safe therapeutic environment is paramount, minimizing anxiety and fostering trust․

Activities might include puppet shows or using toys to represent feelings․ The therapist gradually introduces verbal prompts, starting with simple requests․ Positive reinforcement is key, celebrating any attempt at communication, no matter how small․

Focus remains on comfort and connection, avoiding direct demands for speech․

Specific Therapy Activities – Early Stages

Initial activities focus on non-verbal engagement, play-based interactions, and establishing a secure therapeutic relationship to reduce anxiety and build trust․

IV․A․ Non-Verbal Communication Activities

These activities aim to foster communication without the pressure of speech․ Utilizing gestures, drawing, writing, or pointing allows the child to express themselves comfortably․

Therapists can introduce games like charades or Pictionary, encouraging interaction through visual means․

Creating a “feelings chart” with facial expressions helps identify and communicate emotions non-verbally․

Simple requests, like pointing to desired objects, build confidence․

Gradually, the therapist can introduce minimal verbal prompts alongside non-verbal cues, preparing for eventual verbalization․

The goal is to establish a communicative bridge, reducing anxiety and building a foundation for verbal expression․

IV․B․ Play-Based Therapy for Comfort

Play-based therapy provides a safe and natural environment for children with selective mutism to express themselves without direct pressure to speak․

Utilizing toys, puppets, and imaginative scenarios allows the child to explore emotions and practice social interactions at their own pace․

The therapist observes and gently encourages engagement, building rapport and trust․

Activities like dollhouse play or building with blocks can facilitate communication through role-playing and storytelling․

This approach reduces anxiety and fosters a sense of control, creating a positive therapeutic experience․

Play serves as a bridge to verbal communication, gradually increasing comfort and confidence․

IV․C․ Creating a Safe Therapeutic Environment

Establishing a secure and non-judgmental space is paramount for children with selective mutism․ This involves minimizing pressure to speak and prioritizing the child’s comfort․

The therapist should build a strong rapport based on trust and acceptance, validating the child’s feelings and experiences․

Predictability and routine are crucial, reducing anxiety through a consistent therapeutic structure․

Avoid direct questioning or demands to speak; instead, focus on creating opportunities for comfortable interaction․

Positive reinforcement and encouragement are essential, celebrating small steps and building self-esteem․

A safe environment fosters vulnerability and allows the child to gradually explore communication at their own pace․

V․ Therapy Activities – Intermediate Stages

Intermediate stages focus on gradually increasing verbal participation in less anxiety-provoking situations․ Activities include structured role-playing with trusted individuals, starting with simple exchanges․

Utilizing visual aids like communication boards or picture cards can facilitate expression without immediate verbal demands․

Systematic desensitization techniques are employed, progressively exposing the child to feared speaking scenarios․

Games and playful interactions are incorporated to make practice more enjoyable and less stressful․

The therapist provides consistent support and encouragement, celebrating each attempt at verbal communication․

Success builds confidence, paving the way for more challenging interactions․

Therapy Activities – Intermediate Stages

This section details activities like role-playing, gradual exposure, and visual aids to encourage verbalization in safe, structured environments, building confidence progressively․

V․A․ Gradual Exposure to Speaking Situations

Gradual exposure is a cornerstone of therapy, systematically introducing speaking challenges․ Begin with minimal demands – a nonverbal greeting to a trusted individual․ Progress slowly, adding verbal requests in comfortable settings, like ordering a familiar snack․

Create a hierarchy of situations, from easiest to most challenging․ For example, whispering to a therapist, then speaking to a parent, then to a friend․ Reward each success, reinforcing bravery․ Avoid pressure; allow the child to move at their own pace․ Lunchroom therapy, as noted in resources, can be a practical application․

Remember, the goal isn’t immediate fluency, but reducing anxiety associated with speaking․ Consistent practice and positive reinforcement are key to building confidence and expanding communication․

V․B․ Role-Playing with Trusted Individuals

Role-playing provides a safe space to practice communication skills․ Begin with the therapist, enacting everyday scenarios – ordering food, asking for help, or initiating a conversation․ Gradually involve trusted family members or friends, increasing the challenge․

Scripts can be helpful initially, offering a framework for interaction․ Encourage spontaneity as the child gains confidence․ Focus on non-verbal cues alongside verbal responses․ Positive reinforcement is crucial; celebrate effort, not just perfect speech․

This technique builds comfort and reduces anxiety in anticipated speaking situations, preparing the child for real-world interactions․ It’s a vital step towards generalization of skills․

V․C․ Using Visual Aids & Communication Boards

Visual supports reduce pressure to speak immediately․ Communication boards with pictures representing needs, feelings, or requests empower the child to express themselves non-verbally․ Start with simple choices – “Do you want juice or water?” – pointing to corresponding images․

Gradually introduce more complex boards and encourage the child to initiate communication․ Visual schedules can also ease anxiety about upcoming activities․ Pair visuals with verbal prompts initially, fading prompts as confidence grows․

These tools bridge the communication gap and foster a sense of control, building a foundation for verbal expression․

VI․ Advanced Therapy & Maintenance

This stage focuses on generalizing skills beyond the therapy room․ Practice initiating and maintaining conversations in increasingly challenging settings – a friend’s house, a store․ Social skills training addresses nuances like turn-taking and non-verbal cues․

Role-playing diverse scenarios prepares the child for unexpected situations․ Develop relapse prevention strategies, identifying triggers and coping mechanisms․ Regular check-ins with the therapist ensure continued progress․

Maintenance involves consistent reinforcement and celebrating successes, solidifying newfound communication confidence and preventing regression․

Advanced Therapy & Maintenance

This phase emphasizes skill generalization, social competence, and proactive relapse prevention, ensuring long-term communicative success and sustained confidence in diverse environments․

VI․A․ Generalization of Skills to New Settings

Successfully applying learned communication skills beyond the safe therapeutic environment is crucial․ This PDF outlines strategies for systematically introducing the child to novel settings – starting with less anxiety-provoking locations and gradually increasing complexity․

Activities include pre-visit planning, role-playing potential interactions, and utilizing a support person initially․ The focus is on building confidence to initiate communication with unfamiliar individuals․

Consistent reinforcement from parents and educators is vital, alongside collaborative problem-solving when challenges arise․ The goal is independent, comfortable communication across all life domains, fostering lasting progress․

VI․B․ Social Skills Training

This PDF incorporates targeted social skills training to address underlying deficits that may contribute to selective mutism․ Activities focus on non-verbal cues, initiating and maintaining conversations, and assertive communication techniques․

Role-playing scenarios are central, allowing practice in a safe environment․ Emphasis is placed on recognizing social signals, understanding perspective-taking, and responding appropriately to various social situations․

Visual supports and modeling are utilized to enhance understanding․ The aim is to equip the child with a repertoire of social skills, boosting confidence and reducing anxiety in interactions, ultimately promoting successful social engagement․

VI․C․ Relapse Prevention Strategies

This PDF details proactive relapse prevention strategies, recognizing that setbacks can occur even after significant progress․ It emphasizes identifying potential triggers – new environments, stressful events, or challenging social situations – and developing coping mechanisms․

The document advocates for regular “booster” sessions to reinforce learned skills and address emerging anxieties․ Parents and educators are equipped with tools to support the child during difficult moments, promoting self-advocacy and problem-solving․

A personalized relapse plan is created, outlining specific steps to take if mutism returns, ensuring a swift and effective return to communication․

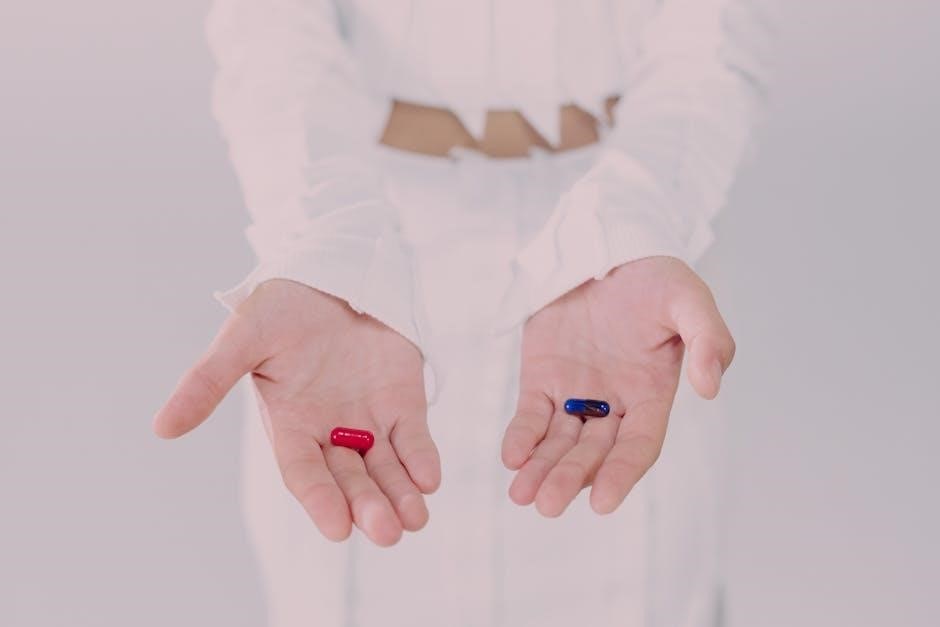

VII․ The Role of Medication

This PDF acknowledges medication isn’t a primary treatment for selective mutism, but can be a valuable adjunct to therapy in specific cases․ It details scenarios where medication might be considered – severe anxiety, lack of response to behavioral approaches, or prolonged struggles with mutism․

The document outlines common medication types used, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), emphasizing they aim to reduce anxiety levels, facilitating engagement with therapeutic interventions․

It stresses the importance of close collaboration between therapists and prescribing physicians, ensuring medication is carefully monitored and integrated into a comprehensive treatment plan․

The Role of Medication

Medication serves as an adjunct to therapy, primarily reducing anxiety to enable better engagement with behavioral techniques, especially in severe or prolonged cases․

VII․A․ When Medication Might Be Considered

Medication isn’t typically the first-line treatment for selective mutism, but it’s considered when behavioral approaches haven’t yielded sufficient progress, or when a child experiences exceptionally high levels of anxiety significantly hindering therapeutic engagement․

Prolonged struggles with selective mutism, despite consistent therapy, can also warrant medication evaluation․ It’s particularly relevant if co-occurring conditions, like severe anxiety disorders, are present․

The goal isn’t to “cure” selective mutism with medication, but rather to alleviate debilitating anxiety, creating a window of opportunity for the child to actively participate in and benefit from behavioral therapy and skill-building activities․

VII․B․ Types of Medications Used

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly prescribed medications for selective mutism, targeting underlying anxiety․ These medications help regulate serotonin levels in the brain, potentially reducing anxiety and facilitating communication․

Other medications, such as selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), might be considered in specific cases, depending on the child’s individual needs and co-occurring conditions․

It’s crucial to remember that medication choices are highly individualized and require careful monitoring by a qualified psychiatrist experienced in treating childhood anxiety disorders․

VII․C․ Medication as an Adjunct to Therapy

Medication isn’t a standalone cure for selective mutism; it’s most effective when used in conjunction with comprehensive behavioral therapy․ The primary goal of medication is to reduce anxiety levels sufficiently to allow the child to actively participate in therapeutic interventions like CBT and exposure therapy․

By lessening anxiety’s grip, medication can create a window of opportunity for the child to practice communication skills and build confidence․ It doesn’t force speech, but rather facilitates engagement with the therapeutic process․

Regular monitoring by a psychiatrist is vital to assess medication effectiveness and adjust dosages as needed․

VIII․ Parent & Educator Involvement

Successful treatment hinges on strong collaboration between therapists, parents, and educators․ Parents play a crucial role in reinforcing therapy goals at home, providing insights into the child’s behavior across various settings, and ensuring consistency in approach․

Educators can create supportive classroom environments by understanding selective mutism, avoiding pressure to speak, and offering alternative communication methods․ Open communication between school and therapy teams is essential․

Parent training and educator workshops can enhance understanding and equip them with effective strategies to support the child’s progress․

Parent & Educator Involvement

This section emphasizes collaborative support, detailing how parents and educators can reinforce therapeutic strategies at home and school for optimal outcomes․

VIII․A․ Supporting Therapy Goals at Home

Consistent reinforcement at home is crucial․ Parents can create opportunities for communication in low-pressure settings, mirroring therapeutic activities․ This includes encouraging verbal responses, even non-verbal ones initially, and positively reinforcing any attempt to speak;

Avoid direct questioning or demands to speak, which can increase anxiety․ Instead, model comfortable communication and create a safe, accepting environment․ Parents should share observations with the therapist, providing insights into the child’s behavior across various contexts․

Engaging in play-based activities and gradually increasing communication expectations can facilitate progress․ Remember, consistency between home and therapy is vital for generalization of skills․

VIII․B․ Collaboration Between Therapists, Parents & Schools

Effective treatment necessitates a collaborative team approach․ Regular communication between therapists, parents, and school personnel is paramount․ This ensures consistency in strategies and a unified understanding of the child’s needs and progress․

Therapists can provide guidance to educators on how to create a supportive classroom environment, minimizing pressure and fostering communication․ Parents act as vital liaisons, sharing insights from home and reinforcing therapeutic techniques․

Joint meetings and shared goal-setting can optimize outcomes, promoting generalization of skills across settings and maximizing the child’s potential for success․

VIII․C․ Creating Supportive School Environments

A nurturing school climate is crucial for children with selective mutism․ Schools should prioritize reducing anxiety-provoking situations and fostering a sense of safety and acceptance․ This includes minimizing performance pressure, such as cold-calling in class․

Educators can implement gradual exposure strategies, starting with non-verbal communication and slowly encouraging verbal participation․ Providing a designated “safe person” the child feels comfortable with can also be beneficial․

Promoting understanding among peers and staff is essential, dispelling misconceptions and fostering empathy․ A collaborative approach ensures a supportive environment conducive to progress․